How New York's subway expansion can pay for itself

Value capture taxes can fund a new era of subway expansion — right now

New York is sitting on an incredible opportunity to fund subway expansion, without having to wait decades for Albany or Washington to find the money.

In 2016, buried in the state budget, Albany gave New York City authority to pay for transit construction by levying extra taxes on increases in property values that result from subway expansion.1 When property values inevitably shoot up around new subway stations, value capture allows the government to recover the costs of construction.

New York has a long list of great subway projects stuck on the drawing board because no one can pay for them. If those same projects could fund themselves using the value they create for local property owners, then we could finally start building again.

This isn’t hypothetical, because mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani is already thinking about these powers. Before winning the mayoralty, Mamdani proposed a state bill to improve the process for using value capture. The bill hasn’t gone anywhere, but it shows he’s thinking about the topic. That shifts value capture from a fun policy idea to a live option.

In this post, I’ll break down how value capture works and what this means for expanding New York’s subway system.

The history and future of the subway

New York’s subway system is old. Of the 476 stations currently open, 66% were constructed over a century ago. Only four new stations have opened in the past 35 years.2

Three of those were part of the Second Avenue Subway project, which in 2017 extended the Q train up Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The 7 train’s station at Hudson Yards is the only other 21st century expansion.

There are many high-impact subway extensions on the MTA’s wish list:

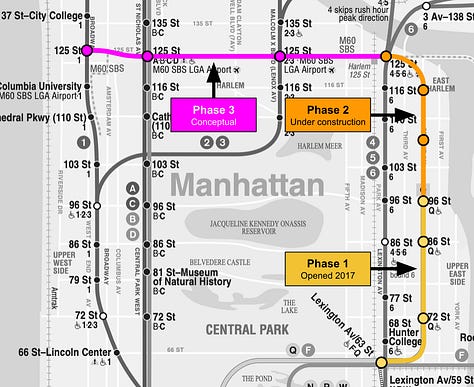

Extending Manhattan’s Second Avenue Subway from 96th Street to 125th Street, and then along 125th Street to Broadway

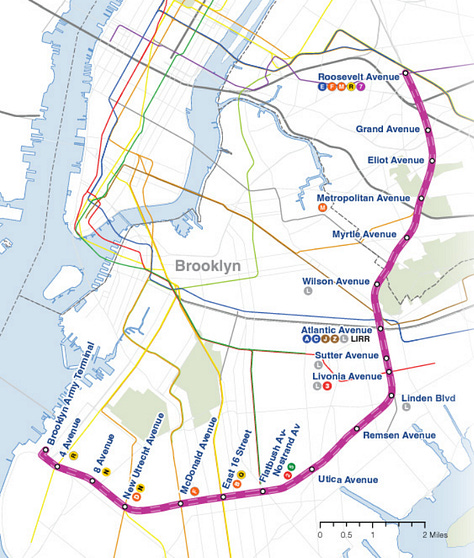

The Interborough Express, connecting Brooklyn and Queens

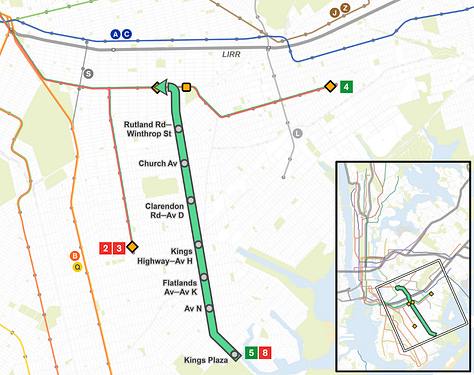

Extending train service along Brooklyn’s Utica Ave

And a dozen more…

The difficulty isn’t identifying good projects; it’s finding the money to pay for them. That’s where value capture can come in.

Good transit increases land value

Property value boils down to access: proximity to jobs, schools, parks, culture, etc. A new subway station slashes travel time to the rest of the city, which is hugely valuable.

We have proof. A study by Arpit Gupta and colleagues at NYU and Columbia found that the 2017 opening of the Second Avenue Subway from 63rd to 96th Street increased Upper East Side property values by $5.9 billion.3

But constructing that subway construction only cost $4.5 billion.

In other words, the subway expansion created more wealth for nearby landowners than it cost to build. Almost all of that windfall went to existing owners, who enjoyed both a more valuable property and a faster commute.

Of course, not all transit projects have such strong return on investment, but New York has a long list of projects that would raise property values — even before considering their value from a transportation perspective.

Value capture 101

Imagine taking a portion of that property value increase, and using it to cover the costs of subway construction. Then we’d be able to afford many more train lines.

Well, it turns out that New York already has a legal framework in place to do exactly this!

The 2016 state law allows the city to levy extra taxes on residential and commercial properties whose values increase as a result of transit expansion. The city can then use the extra tax revenue to pay down the debt incurred by the MTA to fund the subway construction.

No begging in Albany, and no waiting on Washington. Instead, New York City can fund expansions to the subway system ourselves. For any particular project, all the city government needs to do is:

Pass a local law designating the boundaries of the special tax district and establishing the exact parameters of the value capture tax.

Sign a contract with the MTA promising to use the tax revenues to help pay for a specific, identified transit project.

Despite sitting on the books for nearly a decade, the city has never used this power.

Why hasn’t NYC used value capture before?

Most people simply don’t know these powers exist. They’ve never surfaced in a major election or policy debate, and no administration has made them a priority.

Two practical hurdles help explain the inaction: local tax resistance, and the fact that the authorizing law is temporary.

Taxes are unpopular

Nobody likes paying tax. Even in a neighborhood thrilled about a subway extension, hearing “you’ll pay more in property taxes” will provoke instinctive pushback.

Fundamentally, property owners only get taxed on the increase in property values relative to what would have happened if the subway had never been expanded. The property owners didn’t do anything to earn that value, so there’s an element of fairness in taxing those gains.

Additionally, the statute give the city latitude to soften the impact by varying the tax rate and duration. The government can also offer programs for low-income property owners to only pay their tax bill upon selling their home.

The sunset of value capture

The value capture law currently expires in April 2026. It has been renewed in annual increments every year since 2021, despite never being used. That suggests quiet support in Albany, but the one-year cycle is an unstable foundation for long-term planning.

Ideally state lawmakers would give transit planners more certainty by making value capture permanent, or at least agreeing to a longer extension.

Why value capture matters

This is the rare case where the policy exists, the math works, and the politics might line up. Mamdani understands the policy and has already pushed to strengthen it. If his administration wants to add real subway mileage, this is the cleanest path: capture the value that transit creates and reinvest that value to build more.

Value capture can give millions of New Yorkers better access to jobs, leisure, and opportunity, while letting the city control its own future. The only real question is how soon we want to start.

Dig deeper: Read my past posts about fixing NYC’s broken property tax system, how vital transit is to NYC’s economy, and the future of congestion pricing. Or, subscribe for free updates about how NYC works and opportunities to make this city even greater:

Hat tip to Alex Armlovich, who brought this topic to my attention.

The value capture powers were introduced in Part PP of 2015-A9006C, as part of the 2016 New York State budget.

Wikipedia’s list of New York City subway stations. I’ve excluded the South Ferry/Whitehall Street station which “opened” in 2009, but was really a re-opening of previous stations that had existed in a similar location for many decades.

“Take the Q Train: Value Capture of Public Infrastructure Projects” by Arpit Gupta, Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, and Constantine Kontokosta

Thank you! Heard about this for the first time in Ben Max's recently was wondering if there were any longer firm pieces, this is great. I wonder if city council is pro-urbanism enough to make it happen.

Wow. This would be an awesome tax for Zohran to levy, if he has to do that.

That said, I wonder if these projects are slow-moving due to financing or permitting ...